Germantown and Transitional Navajo Rugs and Weavings

The Navajo story behind the use of Germantown yarns actually begins in the mid 19th century in industrial England. An 18 year old English student named William Perkin was in his home workshop completing an assignment from his chemistry teacher, August Wilhelm Von Hoffman. The project was to synthesize a chemical version of quinine from coal tar, a byproduct of the gas lighting industry, to create a synthetic cure for malaria.

Perkin discovered that the cleaning cloths he used were turning a brilliant fuchsia color and were fast to the cloth. He immediately stopped looking for a synthetic cure for malaria, resigned from the Royal College of Chemistry and began producing his dye commercially.

In an age dominated by earth tones and extremely limited and expensive natural dyes, his discovery sparked a European revolution in the new field of chemistry. During the next decade many of these aniline colors were developed and exported throughout Europe and the Americas, quickly replacing what little color was painstakingly wrought from natural resources.

In Germantown, an area by Philadelphia, European immigrants had established a woven cloth industry. These mills quickly adopted the new revolutionary aniline colors. "Germantown" yarns were produced first in 3 ply and later 4 ply formats.

The Navajo, having been conquered in 1864 by Kit Carson, were just returning to their homeland reservation in 1868. Part of the return agreement had the United States government provide annuities for ten years. Besides the much needed sheep, the Navajo received minimal allotments of this new Germantown yarn.

Navajo weavers had plied their skilled craft for hundreds of years prior to their incarceration. Their skill was highly regarded amongst Pueblo and Plains tribes and their blankets were a highly valuable trade item. These new colorful Germantown yarns sparked a revolution in new designs and pattern combinations.

In the latter part of the 19th century, Trading Posts were established on the reservation. These early traders would offer the new Germantown yarns to the best weavers in their respective communities. Traditional weaving was generally limited to natural sheep wool colors and this new pallet of brilliant colors changed Navajo weaving forever.

The fine Germantown tapestries produced by the Navajo women would gain popularity not only with other Native American tribes but also among the encroaching Euro-American population. Train service through the South West in the mid 1880s brought an entirely new market of "tourist" customers and many fine weavings ended up preserved in collections far from their Navajo makers.

In the mid 1880s, aniline dyes became available in a powdered form. Finally, a weaver could use her own sheep wool and dye it into many of these vibrant new colors, creating what are referred to as Transitional weavings. The color revolution was no longer limited to those weavers who were trader supplied with the Germantown yarns. Navajo weaving became over run with brilliant weavings in sometimes garish color combinations. By the early 20th century, the use of aniline colors waned in popularity in favor of a more traditional pallet and aniline yarns receded in overall design.

-

Antique Dazzler Transitional Navajo Blanket - 54" x 84"

Regular price $12,000.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Germantown Navajo Child's Blanket - 24" x 47"

Regular price $3,520.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Germantown Navajo Weaving - 33.5"x55"

Regular price $3,250.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Germantown Navajo Weaving - 41" x 66"

Regular price $13,750.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Germantown Navajo Weaving Dazzler - bound on one end 35.5" x 53" W2038

Regular price $6,000.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

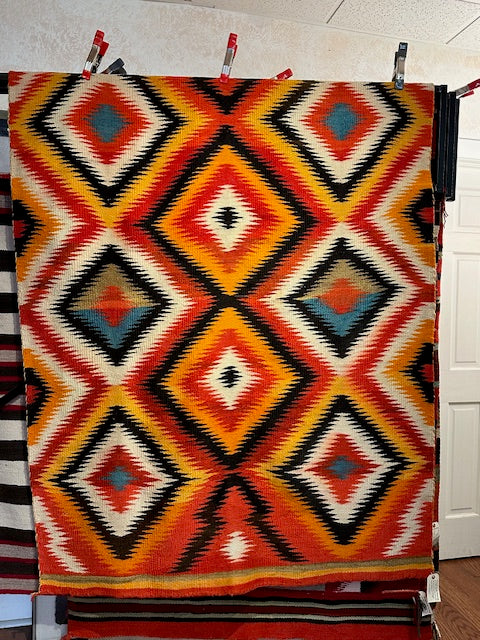

Antique Navajo Eye Dazzler 55" x 79.5"

Regular price $8,250.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Navajo Germantown 3rd Phase Chief's Blanket - 67" x 56"

Regular price $36,000.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Navajo Germantown 3rd Phase Chief's Blanket - 70" x 52"

Regular price $52,000.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Navajo Germantown Child's Blanket - 30" x 51'

Regular price $2,300.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Navajo Germantown Child's Blanket Weaving - 31" x 48"

Regular price $5,100.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Navajo Germantown Dazzler 54" x 73"

Regular price $9,550.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

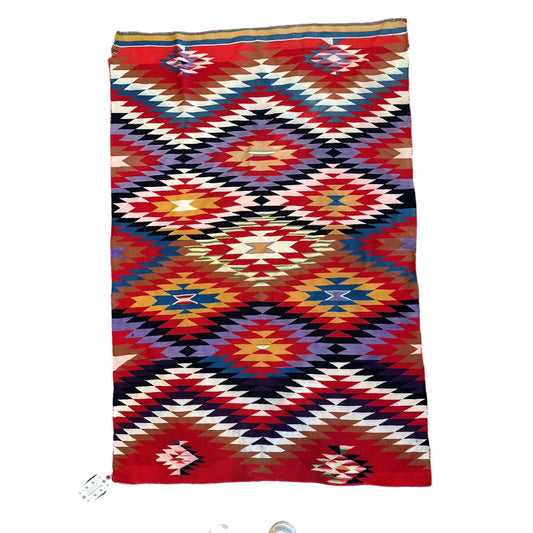

Antique Navajo Germantown Eye Dazzler Weaving - 35" x 54"

Regular price $5,775.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Navajo Germantown Weaving 26" x 47"

Regular price $2,850.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Navajo Transitional Blanket - 53" x 77"

Regular price $7,500.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Navajo Wearing Blanket 42" x 73"

Regular price $4,500.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per -

Antique Navajo Woman's Manta - 56" x 38.5"

Regular price $13,250.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per